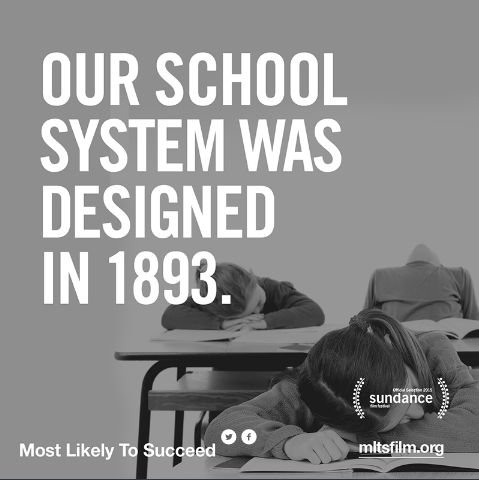

Let me repeat that striking quote in full: “traditional school is actually not helping but imperiling kids.” Ted Dintersmith delivered that powerful message to an audience of teachers and school leaders in his keynote at PBL World 2017. He’s an entrepreneur and innovation advocate, and the producer of the film “Most Likely to Succeed” which was screened later that day. The film has been shown in over 3000 places in the past few years, sparking conversations in communities all over the U.S. about how to change education. Ted also co-authored a book with Tony Wagner, Most Likely to Succeed: Preparing Our Kids for the Innovation Era.

One of the defining issues of our age, Ted says, is the “relentless acceleration of machine intelligence,” which is growing exponentially--which makes it beyond our ability to imagine what kind of change this will bring. Think of the introduction of the smartphone only 10 years ago. So even calls for alarm about X % of jobs being lost in the future are wrong. We just don’t know, but the changes are going to be big and disruptive. Any job that requires pattern recognition, following instructions, or recalling content is in danger of being done by a machine. And yet, that is primarily what our schools still teach.

Think of kids in early elementary school, Ted asked his audience. They’re intellectually curious, they ask questions, they think out of the box. When teachers give kids “genius time” they don’t walk but sprint to pursue their interests. They’ve been given a reason to learn—which they do, becoming experts within days.

But what happens once kids reach high school? Ted told of an 11th grade English teacher who asked students to pick a topic they were interested in to learn about independently. Half the class immediately googled, “What should I be interested in?” Ted noted, “They think whatever they should do is what’s put in front of them… We have to stop crushing the curiosity out of them.”

Where Innovation is Happening in School

Guess what: innovation is being taught in schools that use PBL. Dintersmith pointed to the example of Bismarck, North Dakota (which a few minutes earlier had received the first-ever “PBL District Champion” award from the Buck Institute). “Bismarck could blow you away,” he has told school districts in New York, Boston, and Palo Alto, CA.

He gave the example of an 8th grade project in Bismarck. Students created solar-powered charging stations for homeless peoples’ cell phones. They identified a need, talked with citizens in the neighborhood to hear potential concerns, and used their creativity and innovation skills to design a product that made a difference in their community.

Is the purpose of school to develop students’ potential or to rank them? I noticed a ripple in the crowd when Ted asked this question, pointing out that the latter “advantages the affluent.” He noted the two big innovations in education in the recent past have been more testing, and “the elimination of hands-on, practical learning—but the world needs people who can make things!”

Automated solutions are getting better and better, so how do we teach kids how to leverage machine intelligence? They need to be taught how to work with others in teams, communicate, and see that “a crazy idea out of left field” can become a project. And, Dintersmith claimed, “the amount of learning even in a bad project is enormous.”

Urgent Call for Change in Schooling

Innovation in education will not come easily, Dintersmith admits, but “PBL is indispensible today.” Most adults expect school to be about the same as they experienced it, so we need to show parents that a different approach like PBL works for their kids. “Small steps lead to big bangs,” so teachers can start shifting their practice to PBL and bring colleagues along, since change is contagious. School leaders should give teachers permission to innovate.

Here’s another quote from Ted that struck me hard: “If schools stay the same, I’m not sure civil society will stay together.” He said this six years ago, and NOW he sees that people are coming to understand the truth of it. Amen.