Originally published June 6, 2016 © Edutopia.org; George Lucas Educational Foundation

Last year I took a group of students to Cuba to produce documentaries about the island nation's culture and history. The main objective was learning how to produce documentaries, but one of my students learned a much more powerful lesson through the process. After completing her project, she posted it publicly to YouTube and received critical comments from someone living in Cuba. The feedback from an audience member in another country profoundly affected her, making her aware of what she was missing in her piece, and the impact that her work can have on others.

No test, grade, or teacher evaluation could have come close to helping her learn that deeply, and it made clear to me how important it is for teachers to reexamine why and how we grade our students if we truly care about their success.

As collaboration and project-based learning become preeminent ways of teaching and learning, many teachers struggle with how to evaluate these types of lessons. Traditional methods of evaluation, which have many flaws on their own, are not well-suited for interdisciplinary, multi-modal learning. Teachers need ideas for encouraging students, providing meaningful feedback, and setting students up for success.

Project-based learning (PBL), also known as challenge-based learning, begins with the assumption that there may be more than one right answer. Finding creative solutions to a problem or a driving question is what makes the learning meaningful and lasting, and also difficult to evaluate from a traditional standpoint. When projects are interdisciplinary, it becomes even more of a challenge for teachers to critique subjects that may be unfamiliar.

What to Grade

There are many dimensions of student achievement that we need to evaluate in PBL. The end product is certainly important, but if we focus only on that, the meaningful learning that happens throughout the process can be lost as students feel pressure to do whatever it takes to "make the grade."

The advantage of PBL is that students learn much more than the content. They learn how to work with others, solve problems, present their ideas clearly to an audience, and learn from their mistakes. In other words, we want to acknowledge not only what they learned, but how they came to learn it so that they can use these processes in the future.

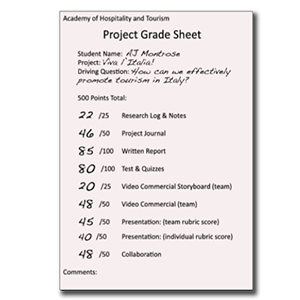

Some areas for evaluation include content mastery, collaboration or participation, and presentation or style. Additional considerations may include meeting deadlines or other elements specific to your topic or project.

How and When to Grade

Rather than setting students up for failure with an antagonistic grading philosophy, set them up for success from the beginning. Establish target goals early to provide purpose for the project, while also establishing expectations of the result:

- What is the problem to solve or the product to create?

- What kinds of subject area content need to be included or addressed in the project?

- What expectations do you have for the final product's presentation, publishing, or performance?

- What kinds of collaborative behaviors must be demonstrated by students throughout the process?

Feedback and corrections should happen frequently to keep students on track, improve their work, and set them up for success in the final product. Waiting too long to give feedback may result in work that is too far gone to be fixed or improved.

What Counts as an Evaluation?

If we understand evaluation as some type of feedback on the progress or achievement of a student, then it can take many different shapes and be as formal or informal as needed. I think evaluations should have four dimensions:

- Self

- Peer

- Teacher

- Audience

While rubric score sheets can be a quick, efficient way of providing feedback to a big class, oral and written feedback is more personal and specific.

Self-evaluation is an especially important piece of the summative evaluation because it taps into higher-level thinking and awareness of the material, process, and final product. It makes students think about their successes, mistakes, and goals for the next time. Choose oral or written form, and include expectations or rubrics for this evaluation.

Peer evaluations are unique to collaborative projects, and I find that they facilitate a better collaborative process because the teacher considers the student experience. We can use this information to modify the workflow for the next project and hold students accountable for their work (effort, constructive contributions to the team, etc.).

Public vs. Private Evaluation

Ideally, PBL is an authentic experience, whether for the class or an audience beyond the classroom walls. So we need to allow for audience feedback to evaluate that project's levels of success. Public critiques (such as comments on blog posts) and class discussion help provide wider perspective and may even carry more meaning for the student than teacher feedback. Consider having a content-area professional or college professor provide critiques for added credibility.

Private evaluations, like self-reflections and teacher feedback, can address confidential information about teammates that allows students to be honest about their peers and themselves. Find a combination of both public and private evaluations that you feel is right for your students or the project.

Constructive Criticism

The goal of evaluations should be to emphasize growth and encourage improvement. There are several techniques that help us in our oral or written constructive criticism.

Critique Sandwich

A negative comment about a problem or flaw is presented between positive comments about something done well.

"I Like That. . ."

Require feedback that includes answers to all of these statements:

- I like that. . .

- I wonder if. . .

- Best next steps might be. . .

Rose/Thorn/Bud

This critique also addresses the good (rose) and the bad (thorn), but also the potential (bud) for what may be a good idea but needs work.

Many of the evaluation methods that I've described are qualitative rather than quantitative, may not be what we're used to, and may not be what your administration requires, so you should find the combination that best suits your needs. But multi-dimensional learning like PBL requires multi-dimensional evaluations that encourage student success.

Michael advises a nationally award-winning broadcast journalism and cinematic arts program in the Los Angeles Area. He speaks regularly on multimedia journalism and technology integration at national conferences like SXSWEdu, ISTE, CUE and the National High School Journalism Convention. His work emphasizes collaborative, interdisciplinary storytelling and how educators can empower students to effect social change. He is an Apple Distinguished Educator, Google For Education Certified Innovator and PBS Lead Digital Innovator.

Website: http://www.michael-hernandez.net